From Gaijin to Local: Navigating 5 Japanese Dating Sites with Ease

There are many good dating sites for a foreigner to use in Japan. Some of the sites are common in the west, and others are specific to Japan.

Ghosting is a very common thing to go through in modern dating. It is especially common in Japan, where they have a very indirect communication style as they're non-confrontational.

Japan has a very short population, which has contributed to the rise in interest of their nation from short manlets in America and Canada. Is 5'8 really that tall in Japan?

Valentine's Day in Japan is largely unique, since the women do all the work. However, the men in Japan have to give gifts in return on a day known as "White Day". Why do the Japanese have these elaborate rituals?

What is the drinking age in Japan? How do Japanese people get around existing laws, and what is to be expected of drunks when in Japan? Find out all of that and more in this article.

I’m SUPER EXCITED to be a writer for JapanJunky. My name is グレゴリー, also known as “Greg”. I recently moved to the Tokyo region on a full visa, after my wife and her partner helped me get the funds together! When you imagine the coolest and most #epic product

Warning Flaggets: Do not read this BASED article The beautiful and sexy city of Tokyo has two distinct flags. One is their ceremonial and stately flag, and the other is their “symbolic flag” - which represents their city internally. The first, with its majestic and beautiful purple background, symbolizes nobility

Japan is not as safe as you may have been led to believe. Many crimes are under reported in the Land of the Rising Sun - mainly because of how many Americans attack underaged Japanese girls.

Do the "Matebo" Laws make it Illegal to be Fat in Japan? Why do you see so few fat people in Japan? Delve into this article to discover the shocking truth.

Japanese Denim is known for being the best in the world. WHY? Because the Japanese put their life energy into the creation of their products. They aren't Cambodian slave children in a factory, they're craftsmen.

What is compensated dating? Have you ever wanted to pay a woman (or man if you’re gay) for companionship, without the benefit of having sex with them? That’s compensated dating. Why do people get involved in doing this? Read this article to find out the hidden secrets of the world of enjo-kosai.

Picture this: You’ve finally crawled out of your gamer hovel and traveled to Japan. Somehow, you’ve managed to pick up a hot Japanese girl (probably using my guide) but UH-OH - you’re currently sleeping in an Amazon approved Sleep Pod and can’t bring her back to

If you’re looking to get a Japanese girlfriend, you’ve come to the right place. I know you probably think that you’ll never stop being an incel, but with my handy five-step guide, you can find a Japanese girl to date you - even if you smell bad and haven’t left mom’s basement since pre-COVID.

So, you want to learn about ancient Japanese Samurai huh? Why? Are you writing a book report on it? Oh - you want to open a successful dropshipping company and you know that the Samurai are the best people to look up to! You are definitely a well adjusted person

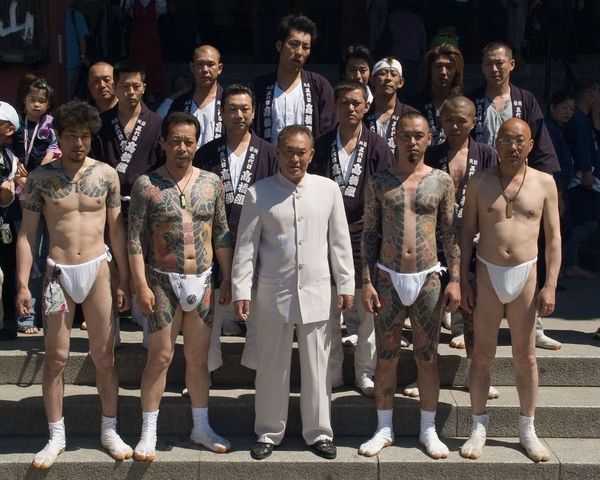

The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, Johnny Mnemonic, Kill Bill, Gokusen, Cowboy Bebop, Nurarihyon no Mago, these movies, TV series, and anime may have different stories but they have one thing in common: the Yakuza or, as we Westerners know it, the Japanese mafia. Many people question whether or

The first thing to greet me when I got off the plane at Narita airport was a large robot dutifully cleaning the floors. That was the start of a trip filled with wonder at Japan’s advanced and highly developed society. Japan has one of the wealthiest and most advanced

From the legendary katana, to the yari spear and naginata blade, to the seemingly endless varieties of bows, arrows and hand-held weapons; these are just a few of the many types of gear and samurai weapons used in feudal Japan. For much of Japan’s history, the country was a

Japan is considered to be under the category of a high context culture, so a lot of the time, you don’t need to explain much because there’s an unspoken understanding between people. It’s easier to say no in Japan than in most Western countries — however, it’s

While it’s been called various names, the Japanese bomber jacket is more famously known as the sukajan. What is it? How did it come about? How do I get one? All the information you need is here — read on to find out!

What kind of behavior could get you into unexpected trouble on your Japanese odyssey? Let’s unpick some of the most commonly discussed weird laws in Japan – and find out which are true and which are simply urban legends. Even if you only know a little bit about Japan, you’

Don’t be surprised if the following overview of ramen makes you a little hungry. If you find yourself with a hankering by the end, we’ve included a simple homemade ramen recipe you can try tonight. The only time I’ve waited in line for over an hour was

When visiting Japan, you’ll surely be tempted by delicious-looking meals that display raw eggs. If you are someone like me, the question "Is it safe to eat raw eggs in Japan?" will pop into your head. With the salmonella scare, it’s a reasonable question to ask! Eggs raised